From Tanzania southward, populations have rebounded, thanks in large part to “buffer” zones that connect more protected areas.

The sun is setting above the horizon in Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, but it’s still 40°C (104°F). A large group of elephants has just arrived at a lagoon to refresh themselves and get their daily dose of water: Drink up 200 liters each, and they are good to go. They frolic a little in the water and then set off to search for leaves and grass in the parched savannah, only to be replaced by another herd with many young calves.

While most species’ populations are decreasing, elephants in southern Africa are doing well. A newly released study of 103 elephant populations from Tanzania southwards — the most comprehensive ever — finds that conservation has halted the decline of savannah elephants in southern Africa over the last 25 years. To be more precise, as of 2020, the elephant population had rebounded to the same number as in 1995: 290,000. The scientists found that large, well-protected areas connected to other protected areas are far better than isolated “fortress” parks at maintaining stable populations.

Even though these outer areas don’t have the same level of protection so animals face a higher risk of dying, they are vital corridors that allow the elephants to migrate back and forth when core areas are too crowded or when facing threats such as poaching or unsuitable environmental conditions.

“Having a mix of areas is key,” says Ryan Huang, the study’s lead author and postdoctoral researcher at the Conservation Ecology Research Unit at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

“To have a stable population, elephants need to be able to flow between good areas in bad times and suboptimal areas in good times.

This model stands in stark contrast with isolated, well-protected “fortress” parks, which lack dispersal opportunities, posing challenges to elephants and humans. With no room to roam, an increasing population of elephants slowly degrades the vegetation and environment within the park and starts visiting nearby areas, which often leads to increased conflict with local communities.

That’s why Huang and colleagues favor a different solution. Besides protecting elephants in national parks, they say we also need to connect these parks so that populations can stabilize naturally. This is known as the core-buffer model, and it’s already being implemented on the ground.

Aprime example of this model’s success is Hwange National Park. Located between the Kalahari Desert and mighty Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe’s largest natural park covers more than 14,600 square kilometers and is ringed with buffer areas stretching another 4,500 square kilometers.

The park is home to the largest population of elephants in Zimbabwe: As of 2022, the population was estimated at 42,000. Besides elephants, the park also has rhinos, lions, leopards, buffalo and wild dogs.

Over the past 25 years, the elephant population in the park has remained stable with small fluctuations. This is mainly due to the fact that elephants here have enough room to roam, and when they need to, they can move into buffer zones or cross to other national parks in Botswana.

Another important factor is that the core is well-protected by about 150 rangers from the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks) who patrol the area, so when elephants feel threatened in the buffer zone, they can retreat to the safe core.

Crushed by negative news?

Thanks to a joint partnership between ZimParks and the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) that began in 2019, rangers are now equipped with a ranger base, enforcement vehicles, canine unit and aerial support through drones. There hasn’t been a single incident of illegal poaching targeting elephants in Hwange National Park since then.

Another contributing factor to the elephants’ well-being is good access to water. The area is extremely arid, but the park management has dug approximately 100 water boreholes throughout the park, which supply water to elephants and other species.

Moreover, Hwange National Park is part of the second-largest nature and landscape conservation area in the world, called the Kavango-Zambezi (KAZA) Transfrontier Conservation Area. This area spans 520,000 square kilometers in five countries — Namibia, Botswana, Angola, Zambia and Zimbabwe — and counts over 20 national parks.

The park is also part of two major wildlife corridors, which are ecologically important wildlife dispersal areas, especially for large mammals, including elephants, buffalo and zebras.

Despite evident successes, the park is also battling with multiple challenges. The carrying capacity has been reached: There are more elephants than this area can sustain in the long-term, and this means elephants need to search elsewhere for food and water.

But the areas where elephants go from here are not exactly safe. Due to a growing human population (Zimbabwe’s population grows at 1.5 percent per year) and government incentives, the buffer areas around the national park are becoming more densely populated and, thus, less elephant-friendly.

Currently, the buffer zones are divided into two categories.

The A1 categories make up about 10 percent of the area surrounding the park.

This is where the government encourages people to settle, build infrastructure, start farming and develop small businesses.

In these areas, elephants and other wildlife have limited space to disperse.

The remaining 90 percent of buffer zones are the A2 categories, where there are fewer people and less infrastructure — but trophy hunting is allowed. This means that while elephants can move in and out of the national park, they face a higher risk when they enter these less-protected areas.

When elephants search for food and water in these areas, they come into conflict with people. They raid their crops and occasionally also attack people, especially when they feel threatened. The park management, together with local residents, is experimenting with different methods to keep elephants away from human settlements. These methods include making natural fences from chili pepper plants and burning a mixture of elephant dung and chili peppers, also known as chili bombs, to scare them away.

“The communities that live around the park need to get value from the wildlife so they consider protecting elephants,” says Henry Ndaimani, landscape conservation officer at IFAW. “Due to ivory bans, there is a downward trend of demand in trophy hunting. As we advance into the future, much more value is going to be derived from photographic safaris.”

Currently, the local people make a living from small-scale farming, carving, tourism and the wildlife sector. To bring people more benefits from living near the national park, the park management has teamed up with IFAW to support alternative livelihoods like climate-smart agriculture, livestock production, domestic water provision and community gardens. They also launched an environmental stewardship program and a scholarship for top students.

The core-buffer model has been adopted in other countries as well, providing benefits to flagship species like elephants as well as other wildlife.

In Zambia, Kafue National Park is a classic example of a core-buffer model, where the core is surrounded by numerous game management areas. This model does not only benefit elephants, but also lions and leopards, whose populations remain stable, and in certain parts of the park, their numbers have even increased.

In Botswana, Chobe National Park has one of the largest populations of savannah elephants in the world, mainly as a result of the core-buffer model and strong enforcement. Just like in Hwange National Park, the core is well-protected — surrounded by large buffer areas — hence making it safe for elephants. Elephants may move freely from core to buffer areas and vice versa when they come across poaching incidents or lack of food or water.

Huang and colleagues have found that even though elephant populations have been stable in southern Africa overall, the dynamic is more complex on the ground.

Some areas, such as southern Tanzania and northern Zambia, still experience severe declines due to illegal ivory poaching.

In contrast, other regions like South Africa and parts of Zimbabwe have seen remarkable increases in elephant populations.

Besides protecting elephants in national parks, Phillip Kuvawoga, director of landscape conservation at IFAW, says we also need to make sure that elephants can live securely in the wider elephant clusters. These are groups of connected parks with elephant populations within a certain region.

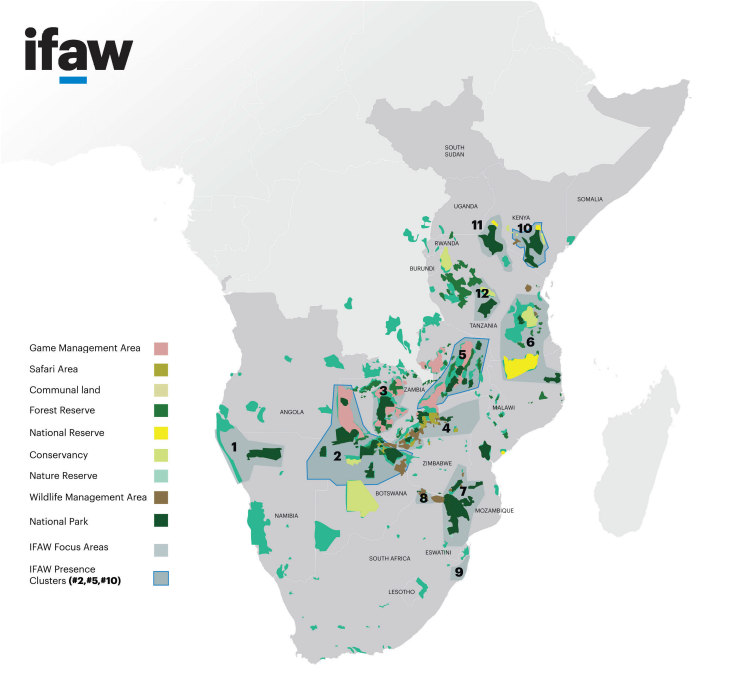

The 330,000 savannah elephants alive today (there were 25 million at the start of the 16th century) live in nine clusters in South Africa and three clusters in East Africa. In 2019, IFAW launched the Room to Roam Initiative, aiming to secure and connect 12 critical landscapes, each home to at least 10,000 elephants.

Their vision comes from 20 years of research on population dynamics of elephant clusters, looking at growth rates, genetic makeup and distribution. IFAW is advocating with governments, communities and other key landscape actors to restore and set aside these areas for elephant conservation.

Kuvawoga is optimistic. “While in India, which is home to 60 percent of Asian elephants and 1.4 billion people, we are talking about ‘room to wiggle,’ here in Africa we still have an opportunity to plan better and bring everyone on board for a common vision for elephant conservation which will be beneficial to other species and people in general,” says Kuvawoga.

Indeed, elephants are a crucial part of a functioning savannah, so a healthy elephant population has cascading positive effects. They disperse seeds, keep savannahs open by preventing encroachment of trees, and create habitats for smaller species, such as insects and lizards. Protecting elephants also helps protect rhinos, buffalo, lions, leopards, hyenas, zebras and other species. Stable and healthy populations of elephants in national parks also bring more income opportunities to local people in the tourism and crafts industries.

Huang and his colleagues have also identified potential suitable habitats with minimal human presence that could be protected in the future. Whether they become buffer areas will depend on the local governance.

“The more humans interrupt the landscape and seclude elephants, the greater danger we place them in,” says Huang. “Working with local communities to develop sustainable models of sharing land is key to the long-term survival of elephants.”